COVID-19 has brought many lessons for urban planners, illuminating existing inequalities and flaws as well as introducing new challenges. One such lesson, as people seek open space and tranquility in tumultuous times, is that parks and natural areas are crucial to our resilience during crises.

The benefits of spending time in nature are well-documented: people with good access to nature tend to live longer lives with fewer physical and mental health conditions. In the short term, spending time in nature can attenuate stress and provide important space for exercise and recreation at a time when many indoor facilities are closed or riskier to visit. It’s no surprise, then, that parks have seen a massive uptick in use during COVID-19, when these benefits are critical for our ability to survive and adapt.

But these benefits are not available to everyone or generated by all green spaces, and that hampers our collective resilience. Poorer neighborhoods generally have less green space than affluent neighbourhoods, and children from nature-deficient areas are more likely to experience health, social and academic performance problems simply because of their postal code. Even when people can access nature, the quality of that green space can vary greatly from place to place, as well as the experience for different kinds of people. Marginalized people must consider additional factors: As a person of color, will a racist person call the police if I go birdwatching? As a woman, can I feel safe walking alone at night? As a disabled person, is the area wheelchair accessible?

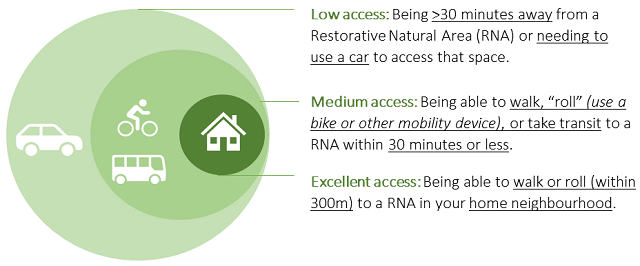

Despite the many variables to “accessibility,” most cities use a simple distance-from-park metric that doesn’t consider park experience or quality. In Vancouver, where I recently spent a summer working with the city as part of the Sustainability Scholars Program, the target is to have all residents live within a “5-minute walk” from a park. But residents who live near the famed Stanley Park (a 4-km² goliath with beaches and towering cedars) have access to something far different than people who live near a small neighborhood park with gravel and a playground. We need a more nuanced and experiential tool for measuring access to nature.

Understanding the Benefits of Green Space

Psychologists say that the mental and physical benefits of nature happen partly because of a reduction in brain and nervous system activity when we spend time there. But what exactly is “nature” and which types of nature trigger that response? While working for the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, I surveyed residents, reviewed policies from other cities and conducted research to find out.

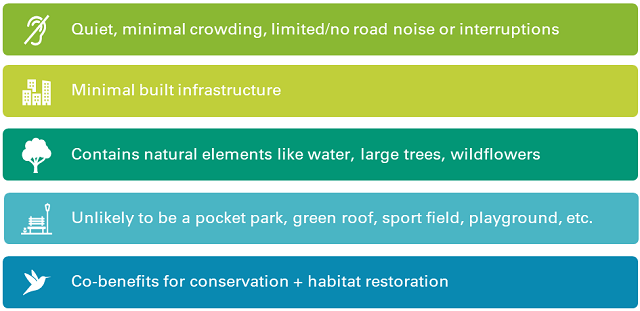

Although we are all different, most of us feel restored by the same kinds of natural spaces. When trying to connect with nature, people tend to prefer large, quiet environments that allow them to temporarily escape from urban life. Things that interrupt and trigger alertness (like blaring car horns, loud music or exhaust fumes) chip away at the restorative potential of the space.

The current tools used by cities to measure access to nature do not capture these experiential distinctions in the quality of a natural space, nor do they reflect the current science on what kinds of natural areas deliver psychological and emotional benefits. In trying to meet the previously mentioned “5-minute walk” target, the City of Vancouver recognized the need for a tool that could more effectively capture qualitative and experiential factors, such as what distinguishes “nature” from any other park.

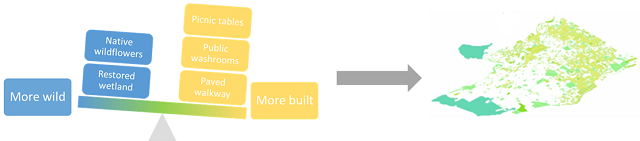

Working with the city, my work focused on answering the question: what is access to nature, and can we map it? Since what counts as “nature” is subjective, that meant underscoring the qualitative and experiential dimensions of what it feels like to spend time in nature and building those elements into a Restorative Natural Area Index. The index can help cities find, build and protect the places that deliver the most benefits for people and nature.

A Restorative Natural Area is a place with lots of natural features and comparatively few distractions. These areas are well-connected, sheltered from traffic and noise, and have plenty of habitat features like large trees and water bodies – simultaneously serving human needs and creating habitats to sustain biodiversity.

Creating a Toolkit for Change

The Restorative Natural Area Index is a mapping tool that can be used in conjunction with efforts to improve equitable access to green space, like the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation’s Equity Initiative Zones, an ongoing effort to identify priority areas for park and open space investment with an eye toward addressing systemic inequities. By creating a map layer focused specifically on the nature dimension of park access (whereas other layers consider things like recreation demand), the index provides valuable additional data to understand the experience and benefits available to residents. The city plans to add the layer to an upcoming update to the Equity Initiative Zones project.

The index can also function as a stand-alone measurement tool and can be constructed by any city interested in doing this sort of analysis using data available through existing municipal repositories, partnerships with academics or citizen science projects.

The Restorative Natural Area Index can help cities weigh natural, restorative landscape features against built-up features to determine the potential of a space to contribute wellbeing benefits. The resulting values can be used to construct choropleth or bivariate choropleth maps – basically, “heat maps” showing higher and lower concentrations of nature experiences in the city. When compared with socioeconomic and demographic data, these maps can be powerful tools to understand and better plan for more beneficial and equitable access to nature.

Using Restorative Natural Areas or similar measurements can help planners and policymakers make the case for building social and ecological resilience in tandem. By planning for more truly restorative green spaces in cities – and more equitably distributed such places – we can grow our resilience to COVID-19 and future crises, while also improving biodiversity and meeting resident needs today. COVID-19 has made everyone more aware of their open spaces, but it’s also opened windows of opportunity to break from bureaucracy and implement rapid change, making now the ideal time to revisit how we plan for access to nature.

Jo Fitzgibbons is pursuing PhD research on the governance of urban greening at the University of British Columbia and recently completed a work term with the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, where her work focused on defining and measuring access to nature.